Have you ever lent a book to a friend . . . who never returned it? Have you ever lent a book to a friend . . . who marked up your book, or let the children tear pages, or worse, let the dog chew on the bindings? Here's your revenge: Remind them of what awaits them if you don't receive it back from them in the same condition in which you lent it!

The following is copied from the Medieval Manuscripts and Earlier website of the Medieval Manuscripts blog

Enjoy!

The following is copied from the Medieval Manuscripts and Earlier website of the Medieval Manuscripts blog

Enjoy!

Angel of Death Conquered - Rome, Italy

Angel of Death Conquered - Rome, Italy The Curse of the Spiritual Sword

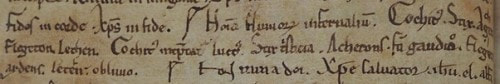

We have previously reported about our fascination with medieval book curses, added in monastic libraries to ward off thieves and warn careless users. Book curses typically state that those who stole or damaged a book would be spiritually condemned, often including the Greek-Aramaic formula ‘Anathema Maranatha'. For example, during the 12th and 13th centuries monks at Reading Abbey systematically added such curses to their manuscripts containing biblical commentaries (examples include Add MS 38687, Harley MS 101 and Harley MS 1246).

Reading Abbey’s book curse in a commentary on Deuteronomy and Joshua (1st quarter of the 13th century): Add MS 38687, f. 150r

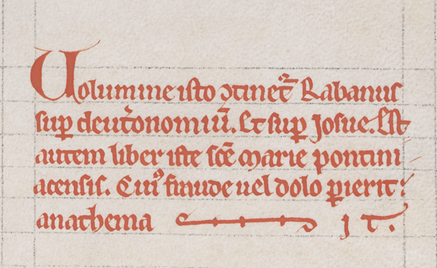

Reading Abbey’s book curse in a commentary on Deuteronomy and Joshua (1st quarter of the 13th century): Add MS 38687, f. 150r We would like to share some new findings that will enable you to protect your favourite books, as well as other prized possessions. One example comes from the so-called ‘Noyon Sacramentary’ (Add MS 82956). This 10th-century manuscript, produced by the monastic community at Noyon Cathedral in northern France, contains masses and prayers for blessings and ceremonies. The manuscript opens with a wrathful curse that would bring down a series of spiritual punishments upon those who stole from or committed any other crime against Noyon Cathedral.

Noyon Cathedral’s ‘Curse of the Spiritual Sword’ (4th quarter of the 10th century): Add MS 82956, f. 1v

Noyon Cathedral’s ‘Curse of the Spiritual Sword’ (4th quarter of the 10th century): Add MS 82956, f. 1v The Noyon Cathedral curse begins: ‘excommunicamus eos et gladio sancti spiritus a vertice capitis usque ad plantam pedis transverberamus’ (‘We will excommunicate them and cut through them with the sword of the Holy Spirit, from the top of the head to the sole of the feet').

It then declares that book-thieves would be condemned to burn in the eternal fire of Hell together with Judas Iscariot, perhaps because they, like Judas, committed betrayal for material gain. Finally, to top it off, these thieves were to remain in the darkness of Hell where they would keep the devil company.

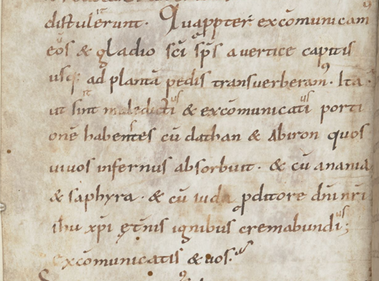

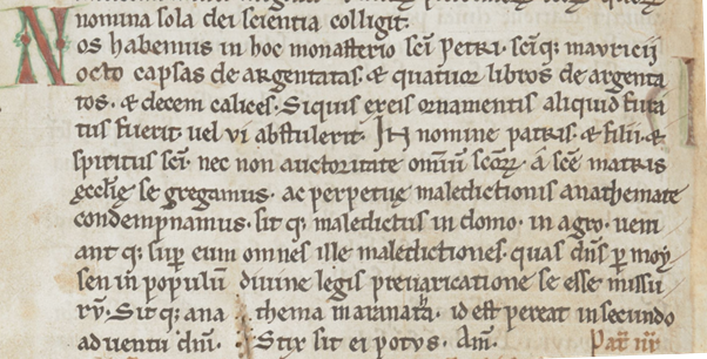

Perhaps an even more powerful curse for protecting your belongings comes from a 12th-century lectionary (containing readings from the Gospels for the Mass) from the Benedictine abbey of Tholey in western Germany (Add MS 29276). The curse is preceded by an itemised list of the monastery’s relics and sacred objects: ‘We have in this monastery of St Peter and St Mauritius eight bookcases of silver, four books of silver, and ten chalices’. Protecting this treasure is a curse that the community would collectively cast upon anyone who stole from the monastery:

‘a sancte matris ecclesiae segregamus ac perpetuae maledictionis anathemate condempnamus . sit que maledictus in domo . in agro . veniantque super eum omnes ille maledictiones . quas dominus per moysen in populum divin[a]e legis prevaricatione se esse missurum. Sitque anathema maranatha . id est pereat in secundo adventu domini. Stix sit ei potus. Amen’.

‘We will segregate him from the mother church and condemn him with the eternal curse of anathema: may he be cursed in the house and on the land, and let all the curses that the Lord cast through Moses onto the transgressors of the Divine Law come upon him. May he be anathema maranatha. That means: may he be damned at the Second Coming of Our Lord (the Last Judgement); may the Styx be his drink. Amen’.

Tholey Abbey’s ‘Styx-Curse’ (c. 1100–c. 1175): Add MS 29276, f. 162v)

Tholey Abbey’s ‘Styx-Curse’ (c. 1100–c. 1175): Add MS 29276, f. 162v) This curse encompasses both the eternal sentence to Hell, at the Last Judgement, and the Styx, the principal river of the Underworld. While it may seem unexpected to find a medieval monk referring to the Styx, monasteries gained knowledge about the Underworld through their copies of works such as Virgil's Aeneid. For example, in a 12th-century theological miscellany from the Cistercian abbey of Thame in Oxfordshire (Burney MS 357), the Styx is listed as one of the rivers in Hell, and its name is defined as ‘sadness’ (tristicia).

It's clear that some medieval monks were very resourceful when it came to protecting their most precious treasures. The book curses that they devised indicate not only their knowledge of religious and Classical works, but also the importance they attributed to their sacred books and objects.

To learn more about medieval monastic libraries, and how books were acquired, used and stored, see this article on Medieval monastic libraries by Alison Ray, created as part of The Polonsky Foundation England and France Project: Manuscripts from the British Library and the Bibliothèque nationale de France, 700–1200. Together with the Bibliothèque nationale de France, we have digitised 800 manuscripts from our collections, which you can learn more about on our dedicated Medieval England and France webspace.

Clarck Drieshen

Follow us on Twitter @BLMedieval#PolonskyPre1200

Part of the Polonsky Digitisation Project

In partnership with

Supported by

Posted by Ancient, Medieval, and Early Modern Manuscripts at 12:01 AM

Tags

Manuscripts, Medieval, Medieval history, Polonsky

Copyright © The British Library Board

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2019/06/the-curse-of-the-spiritual-sword.html